Designing and creating motorcycle fairings is a sophisticated process that combines art and engineering, making it imperative for business owners in the motorcycle industry to understand the nuances involved. Fairings are essential for the motorcycle’s aerodynamics, protection, and overall look. This article serves as a comprehensive guide, starting with effective design techniques to meet user needs and aesthetic preferences, followed by material selection that balances cost and performance, and concluding with fabrication techniques that bring designs to life. Each chapter will delve into these crucial components, equipping you with the knowledge needed to embark on motorcycle fairing production successfully.

Shaping Speed: The Integrated Art and Engineering of Motorcycle Fairings

The fairing is not merely a shell that dresses a motorcycle; it is a carefully engineered interface between rider, machine, and the air that surrounds them. When you set out to understand how to make motorcycle fairings, you enter a realm where aesthetics, aerodynamics, thermal management, structural integrity, and practical usability converge. A well-conceived fairing can transform a bike’s character—reducing rider fatigue on long rides, guiding airflow to minimize drag, and shielding sensitive components from heat and debris—while still honoring the rider’s vision for style. This blending of form and function is the throughline of a design process that begins long before any material is cut and continues long after the final paint cures. To approach fairing construction with discipline is to acknowledge that each decision reverberates through performance, safety, and the daily experience of riding.

Designing motorcycle fairings starts with a clear understanding of the bike’s intended role. Touring machines demand generous wind protection, quiet airflow, and stability at speed, often achieved with fuller, more enveloping shapes that smooth the transition of air around the rider’s body. Racing-oriented fairings, by contrast, are tuned for lightness and agility, with sculpted surfaces that reduce weight and optimize air separation at higher speeds. A single concept can be refined into multiple variants depending on desired outcomes: maximal wind damming for comfort, or optimized streamline for speed and handling. In both cases, the rider’s position, line of sight, and ergonomics are essential inputs. The rider’s silhouette, the cockpit’s openness, and even the transition from the fairing to the windscreen become parameters that a designer must respect as part of the geometry of performance.

An important thread in the design phase is fitment. A fairing must align with the motorcycle’s frame and existing hardware, from mounting points to radiator intakes, and it must accommodate wheels and suspension travel without creating unintended contact or vibration pathways. This is where the concept of clear communication reveals its central importance. The designer’s sketches or CAD models communicate intent to fabricators and clients, but the final product depends on a shared understanding of tolerances, material behavior, and installation realities. It is not unusual for a project to begin with rough geometry and iterate toward a solution that offers both ideal aerodynamics and practical assembly. When a client asks for custom graphics or painted finishes, the conversation must extend beyond lines and curves to consider how color and texture interact with lighting, reflections, and wear. A well-documented design brief—though it starts as a sketch—will evolve into a precise specification that governs every subsequent phase, from mold making to final coating.

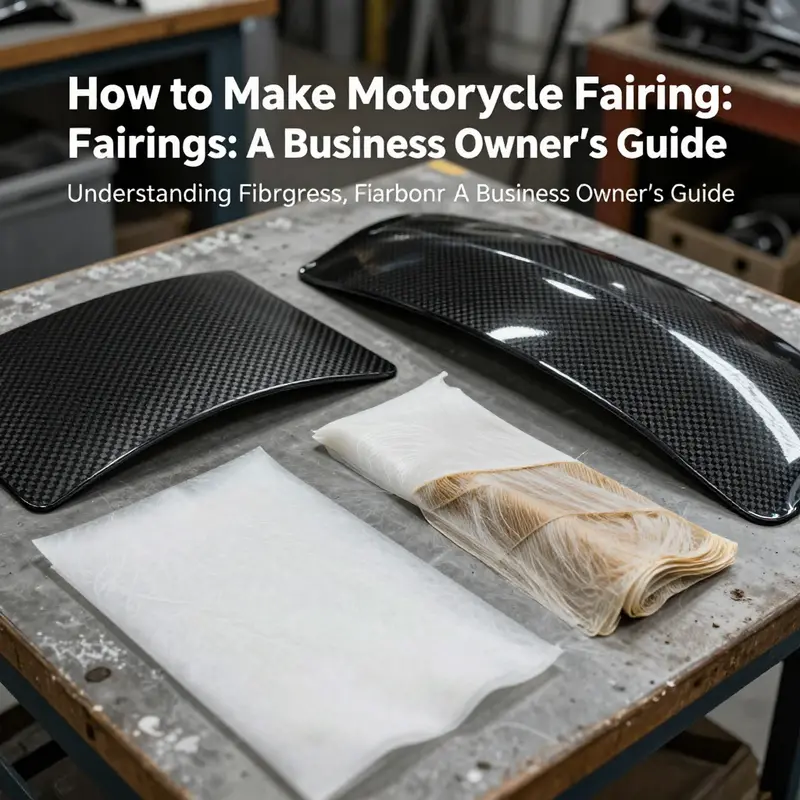

Material choice is the hinge on which many decisions swing. The tradeoffs among fiberglass, carbon fiber, and various plastics are fundamental. Fiberglass is forgiving and approachable; it accepts layups that can be cured with simple tooling setups, and it offers enough strength for many touring and sport-touring projects without the prohibitive cost of carbon fiber. That said, it requires careful resonance control and a rigorous finishing process to ensure a smooth surface ready for paint. Carbon fiber, with its remarkable strength-to-weight ratio, stands out for weight-conscious builds and high-performance applications. It demands skill and discipline, particularly in layup and curing, with attention to resin systems, vacuum techniques, and thermal management during cure. Plastics such as ABS or polycarbonate present a different set of conveniences: ease of heating and forming, straightforward repairability, and strong compatibility with rapid prototyping or productionization, though they may not match carbon fiber or fiberglass for stiffness and long-term heat resistance in some configurations.

Durability also hinges on how the fairing interacts with heat and vibration. Engine heat and exhaust manifolds can impose thermal stresses on surface finishes and structural joints. A practical approach to heat management is to integrate heat shields or strategically route airflow so that heat-sensitive components and electronics remain shielded from radiant heat while maintaining predictable cooling patterns for the engine and radiators. The inclusion of a heat shield in the design is not merely a protective feature; it is a design decision that affects the fairing’s geometry, mounting strategy, and even how the surface is treated for paint adhesion and wear resistance. When the rider spends long hours in the saddle, the fairing’s ability to minimize buffeting and to direct air cleanly around the torso becomes a matter of comfort and endurance.

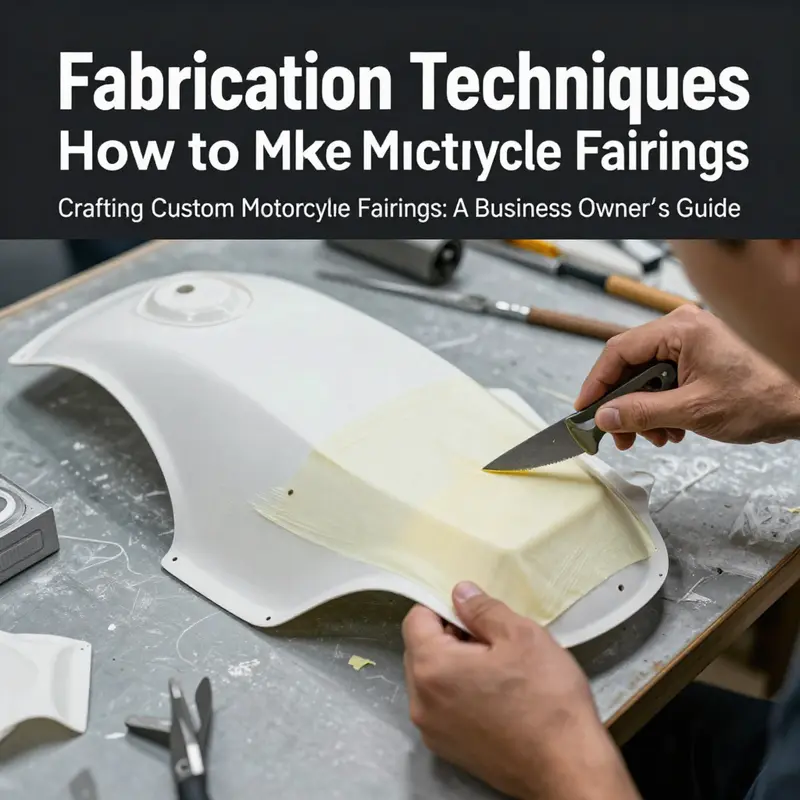

With an informed sense of use and material behavior, the process naturally moves toward prototyping and molding. In traditional fairing workflows, a three-dimensional concept is translated into a tangible plug—often a full-scale foam or clay model—that captures the intended curvature, edge quality, and transition lines. This plug serves as the master for the negative mold, typically fashioned from fiberglass, silicone, or a hard mold material. The mold itself becomes a carefully controlled environment where dimensional stability matters. Any shrinkage, surface imperfections, or misaligned alignment guides in the mold will propagate into the final fairing parts, undermining fitment and aesthetics. Thus, precision in the mold stage is a prerequisite for success in the subsequent fabrication steps.

The fabrication phase is where the design takes physical form. For fiberglass, a resin-soaked cloth is laid into the mold with deliberate layering to build strength where the structure needs it most. Curing conditions, resin choice, and the sequence of cloth plies influence the piece’s rigidity, impact resistance, and surface finish. Once cured, the part must be carefully sanded, trimmed, and seam-bonded with attention to fiber alignment and resin-rich areas that could introduce weak points or paint lift in the finish. For carbon fiber, the process becomes more exacting. Pre-preg or wet layups require a controlled environment and sometimes vacuum pressure to achieve uniform distribution of resin and high fiber-to-resin ratios. The resulting part is typically lighter and stiffer but demands meticulous craftsmanship and quality control to avoid voids or misweaves that can compromise strength and appearance. Plastic fairings, formed by heating and draping over the mold, bring a different rhythm to production. They are generally faster to produce and easier to repair, but their performance in terms of rigidity and impact resistance can be more sensitive to heat deformation and UV exposure, which informs both their design and surface finishing strategies.

Across materials, bonding joints and interface seams demand particular care. The choice of bonding methods—whether mechanical fasteners, adhesives, or a combination of both—depends on the material system and the expected load paths. For example, fiberglass and carbon fiber parts commonly employ careful bonding and mechanical fasteners to distribute loads across larger areas, while plastics might rely more on heat-staked or snap-fit joints in addition to adhesive bonding. The goal is to create assemblies that maintain alignment under vibration, resist cracking around mounting points, and allow for some serviceability when panels need removal or repair. In all cases, the hardware chosen must be corrosion resistant, compatible with the fairing material, and accessible for maintenance without requiring disassembly of major components every time a panel is removed.

Finishing and painting complete the transformation from a functional shell to a durable, expressive piece of the motorcycle. Surface preparation begins with smoothing the cured part to remove tactile imperfections and to create a uniform base for primer. Primers not only improve paint adhesion but also help reveal any residual flaws that benefited from additional sanding. The color layer follows, where the artist’s hand and the technical team’s guidelines converge. Color matching is not merely about a single hue; it encompasses how color interacts with lighting, reflections, and the bike’s overall palette. Clear coats serve multiple roles: they protect the artwork from UV exposure and environmental wear, provide gloss or satin finishes according to the desired aesthetic, and help seal the surface against micro-scratches and minor abrasions. Graphics and decals, if included, require precise registration and careful protection during subsequent clear coating. The relationship between base color, clear depth, and gloss control shapes the perceived quality of the final piece. For many builders, a well-executed paint job is as vital as the structural integrity of the panels it covers, because it communicates the rider’s taste and the project’s narrative while bearing up to the inevitable realities of road use.

A critical stage in any custom fairing project is alignment and test fitting. The fairings must mate with the frame cleanly, with even gaps at edges, and with controlled airflow around the rider’s body. Every edge line and corner radius influences how air streams around the bike, affecting drag and buffeting. The fairing’s bottom edge, for instance, should present a gentle facing surface to the front wheel to avoid turbulence that could degrade stability. The installation phase also requires rigorous checks for clearance: is there adequate space for the suspension movement, brake lines, and cooling fans? Do the panels interfere with handlebars or rider inputs when the steering is turned to full lock? Do mounting points line up with aftermarket brackets or OEM brackets without requiring rework of the bike’s substructure? These checks are not punitive; they are essential for ensuring safety and ride quality. If issues surface, the design or the mounting strategy can be iterated, sometimes necessitating minor reshaping or relocation of attachment points. In professional contexts, this iterative process is part of a formal testing protocol that includes visual inspection, tactile assessment, and, where possible, wind tunnel or computational fluid dynamics evaluation to confirm that the final geometry achieves the targeted aerodynamic profile without compromising structural safety.

Beyond the technical, the fairing is a canvas for personal expression. A well-executed graphic scheme can harmonize with the bike’s lines, emphasize its silhouette, or tell a story about its owner or inspiration. The painter or graphic designer might collaborate with the original designer to ensure that the final finish reads correctly from multiple viewing angles and under different light conditions. The collaboration between designer and client, and the clarity of communications about color placement, curvature emphasis, and even micro-details like edge bevels or texture finishing, are what elevate a good fairing to a memorable one. Graphics decisions must also consider durability: whether the finish is a translucent layer over a base coat or a full-coverage color with a protective clear, the method should resist road grime, stone chips, and sun exposure while preserving the desired depth or metallic effect.

As in any craft, practical constraints must be acknowledged. The wheelbase, weight distribution, and braking performance all influence fairing geometry. A taller, broader fairing may improve rider comfort but at the expense of increased weight or balkier access to maintenance areas. The structural design must avoid creating fragile points at high-stress edges where panels are bonded or mounted. Moreover, the project must respect safety standards and the requirements of the rider’s insurance or warranty constraints. A poorly executed modification can alter weight distribution, block essential airflow to radiators, interfere with steering geometry, or create blind spots or mounting hazards. In many respects, the responsible approach to fairing fabrication mirrors responsible driving: safety through design integrity as much as aesthetics.

The landscape of fairing design is enriched by the broader ecosystem of reference images and case studies that designers use to inform their own work. Visual libraries—whether in physical portfolios or digital boards—offer a wealth of configurations, from sleek, race-inspired shapes to rugged, tour-ready shells. A key takeaway from these explorations is that durability and compatibility should never be afterthoughts. The structural composition of fairings in production models is deliberately chosen to withstand the rigors of long-distance riding and variable climates, while still presenting a polished, cohesive appearance. In practice, this means evaluating how a given material behaves under repeated temperature cycles, exposure to moisture, and potential impact from road debris. The goal is to strike a balance where the fairing remains light, strong, and visually compelling while integrating smoothly with the motorcycle’s existing systems and the rider’s daily routine.

In contemplating a design or embarking on fabrication, many riders benefit from looking at existing categories and their respective strengths. For example, a touring-oriented approach favors larger, more enveloping forms designed to funnel air around the rider rather than simply over the bike. A sport-oriented approach, by contrast, might emphasize tighter lines and sharper edges that promote faster air separation and less drag. The design language chosen communicates not only the rider’s intent but also the engineering discipline behind the build. When a client asks for customization, this is where the designer’s creative and technical fluency must meet the client’s taste and expectations. The ability to sketch, to simulate, and to prototype in stages—while maintaining a clear narrative of why each choice matters—turns a project from a collection of panels into a coherent performance asset.

For readers seeking practical pathways beyond theory, one pragmatic route is to start with a well-curated reference library of shapes and finishes. Tools like mood boards, CAD previews, and physical foam or clay models enable early testing of fit and form before any material is cut. A strategic approach uses a modular mindset: designing with panels that can be swapped or upgraded as the rider’s goals evolve. This modularity can simplify future maintenance or customization, allowing a rider to change the look or functionality without redoing the entire shell. It also lends itself to iterative testing, where small changes in curvature or edge geometry are evaluated against comfort and aerodynamics, rather than committing to a single monolithic idea from the outset. Such an approach respects both the artistry of design and the pragmatics of real-world riding.

In the broader ecosystem of resources and communities, collaboration matters. Designers, fabricators, and riders can learn a great deal from one another by sharing prototypes, testing notes, and ride impressions. Curated boards and galleries often become engines of inspiration, offering a visual vocabulary that translates across different bike models and riding styles. If a reader is exploring how to make motorcycle fairings, the practice is not just about technique; it is about cultivating a shared language that communicates intent, performance criteria, and aesthetic preferences. The journey from concept to finished panel is a narrative of problem-solving, craftsmanship, and a careful balancing of weight, rigidity, and airflow. When done well, a fairing becomes more than a protective shell; it is a statement about what the rider values most in the experience of riding—a blend of speed, comfort, and personality expressed through form, material, and finish.

For readers who want a curated starting point in the practical realm of parts and components, exploring a dedicated catalog of aftermarket or OEM-inspired fairing categories can be helpful. A relevant reference point in this regard is a specific fairings catalog that concentrates on Honda models, which offers a spectrum of shapes and mounting considerations. This resource can serve as a useful benchmark for proportion, line, and surface treatment as you begin to translate concept into concrete panels. While the catalog you consult may reflect a particular design language, the underlying principles of fitment, material behavior, and finishing quality remain broadly applicable. The key is to absorb successful design cues while adapting them to your own bike and your chosen material system. When you study a catalog or gallery, look for how edge radii are treated, how transitions between panels are handled, and how the surface serves both aerodynamic and aesthetic purposes. These elements—handled with care—are the micro-decisions that accumulate into a coherent, confident final product. If you are seeking a reflective starting point, consider how a given design language handles the clash or harmony between lines and planes, and how the color and texture choices interact with light across a moving surface. In practice, this means focusing on line, proportion, and surface continuity, rather than merely chasing the latest visual trend.

In the end, the art of making motorcycle fairings sits at the intersection of design intent and engineering discipline. It asks for a patient, iterative approach that respects the bike, the rider, and the material realities of fabrication. The projects that endure are those where the designer translates complex performance criteria into tangible shapes and build processes, then tests, tweaks, and refines with eyes toward safety, durability, and the rider’s experience. The narrative of a fairing is, in truth, the narrative of riding itself: a continuous dialogue between wind, motion, and the human desire to blend speed with comfort—a dialogue expressed not only in curves and colors but in the quiet confidence of a panel that fits perfectly, shields well, and looks unmistakably aligned with the bike’s spirit.

Internal link reference for inspiration and broader context: for readers interested in a catalog that emphasizes Honda fairings, see the Honda fairings category. Honda fairings category.

External resource for further technical grounding: https://www.bmw-motorrad.com/en/motorcycles/road/r-1150-rt.html

Choosing the Skin of Speed: Material Truths Behind Motorcycle Fairings

The fairing on a motorcycle is a study in balance. It must slice through air with minimal drag, shield the rider from wind and debris, and carry the design language that defines a bike’s character. In the workshop, the material you choose becomes the backbone of every subsequent decision. It dictates how the part behaves at speed, how easily you can shape or repair it, and how your finished piece will age in sun, rain, and the thousand highway miles ahead. When the topic is how to make motorcycle fairings, material selection is not a single checkbox to tick. It is a conversation about trade-offs, performance goals, and the realities of cost and craft. The narrative here is not only about what to pick, but why those choices matter, how they influence every stage from concept to ride, and how you can translate a design vision into a strong, predictable fairing that fits your bike and your riding life as cleanly as possible.

Design and material choice arrive in a single, inseparable moment. Aerodynamics sets the ceiling for what the fairing must accomplish: smooth surfaces that guide flow, minimized separation, and controlled pressure distribution around the rider and engine. Structural integrity sets the floor: the part must resist deformations from wind loads, vibration, and minor impacts, while still being light enough to not offset the performance gains you seek. Manufacturing practicality fills in the gap between vision and reality. A design that looks spectacular on screen can crumble in a mold or warp under heat in the workshop if the material and process don’t align. It is here, in the crucible of design intent and material science, that fiberglass, carbon fiber, and plastics reveal their strengths and their limits.

Fiberglass stands as a workhorse for custom and aftermarket fairings. It is a composite built from glass fibers embedded in a polyester or epoxy resin. The math behind fiberglass is honest: it offers a favorable combination of rigidity, formability, and cost. For a custom project, fiberglass is forgiving. The cloth is laid into a mold in layers, resin is worked through, and after curing you can sand, fill, and shape toward a refined surface. The advantages show up in real-world terms. Fiberglass parts are relatively easy to repair. A crack can be ground out, a new layup applied, and the piece can return to service without the kind of specialized equipment that carbon fiber demands. The material is light enough to deliver a noticeable improvement over solid plastics in terms of weight, yet it remains accessible to hobbyists and small shops with basic tooling.

But fiberglass has its own compromises. The finish can be less drapable and uniform than plastics when you’re chasing razor-straight lines or feather-thin edges. The resin system, while strong, is susceptible to humidity and UV exposure over long periods. Repairs, though straightforward in concept, require skill to avoid a mismatch in texture or a perceptible seam. The cost benefit is clear, but it often demands more labor than a ready-made plastic shell. For riders who want to prototypes and iterate quickly, fiberglass offers a forgiving gateway into fairing fabrication. It is also a wise choice when the goal is to maintain or repair complex curves without escalating material costs. The craft of laying up into a foam or clay plug, building a mold, and then producing the final part reinforces that sense of craft: you can see the psychology of the material in the way it responds to heat, resin, and pressure, as if it were a partner in the design rather than a passive substrate.

Carbon fiber represents a different philosophy of speed. It is where the performance conversation tilts toward the physics of strength and weight. Carbon fibers, woven into fabrics and infused with resin, yield a part with a higher strength-to-weight ratio than fiberglass and a rigidity that helps with precise handling at high speeds. The characteristics are seductive: a stiffness that translates into more predictable turn-in, a memory of shape under load, and a finish that many riders associate with advanced engineering. The aesthetic payoff—those dark, glossy weaves—also communicates performance intent in a way that plastic can rarely match. Yet carbon fiber is not a material you simply choose for a casual build. The economics of carbon fiber fairings are demanding. High-quality CFRP parts often require precise layups, controlled curing environments, and sometimes an autoclave or vacuum integrity processes. The tooling, prepreg materials, and labor costs push carbon fiber into the realm of premium or race-focused applications. Even for ambitious enthusiasts who want to push weight reduction, the feasibility of doing carbon fiber at home depends on access to equipment, expertise, and the tolerance for longer lead times.

The plastics most commonly encountered in production fairings are ABS and polycarbonate blends. Plastics offer an unusual blend of resilience, ease of manufacturing, and durability. ABS, in particular, has become a staple in OEM and aftermarket fairings because it is tough, impact resistant, and relatively forgiving to mass production methods. The ability to thermoform or heat-shape these materials into complex shapes—via resin transfer methods or simple heat bending—makes plastics especially friendly for prototyping and for riders looking to interchange parts without a heavy investment. Plastics can hold color and gloss well, tolerate UV exposure with stable long-term performance, and resist weathering. They can be cost-effective to replace, which matters when a rider wants to preserve the overall visual identity of a bike without breaking the bank.

Still, plastics have limits. They can be heavier than carbon fiber for the same strength requirements, and their stiffness is not on par with carbon fiber in the most demanding performance contexts. Impact resistance is excellent, but the stiffness-to-weight ratio is lower, which can translate into a different feel at high speed or in high-load cornering. The surface finish, though robust, may not reach the ultra-high gloss or the micro-scratches of CFRP when polished. The repair path for plastics is often straightforward—patch and replace in a fashion similar to OEM parts—but the repair story for a curved, multi-piece fairing can become complex if you’re chasing a seamless look. Each material thus expands or contracts the range of design choices you can safely pursue, affecting how thin a section can be, how sharp a line can be cut, and where you place cutouts for headlights, vents, or mounting hardware.

The truth of material selection, then, lies in balancing performance targets against workability and budget. A high-performance rider who seeks meaningful weight savings and a certain aesthetic may lean toward carbon fiber, accepting the higher cost and greater manufacturing complexity. A rider who values ease of fabrication, repairability, and a friendly entry point might choose fiberglass for the bulk of the bodywork, reserving CFRP for accents or critical load-bearing areas. A commuter rider aiming for durability, ease of replacement, and a broad availability of parts in the aftermarket might default to ABS plastics, knowing that the mass production heritage of plastics comes with predictable performance and predictable supply chains. These choices reflect a broader principle: fairings are not merely shells; they are engineered systems that interact with the motorcycle’s frame, steering geometry, and rider posture. The material you pick interacts with these elements in tangible ways, from how the panel flexes under wind gusts to how it mates with the belly of the bike at the fairing edges.

With the conversation about material choices comes the practical arc of making: from concept to mold, to layup, to a finished part ready for paint and fitment. In a typical workflow, the design begins with a detailed plan in CAD or a carefully crafted hand-drawn sketch. The shape is not just about aesthetics; it is a statement of how air will travel over the bike and how the rider will experience turbulence, pressure, and lift. Once a shape is defined, a plug or master model is created, often from foam or clay, to capture the volume and curvature that the final fairing must deliver. The plug becomes the prototype on which the negative mold is built. Here the material choice begins to shape the process. A fiberglass layup can be done with readily available resin systems and fabric, while carbon fiber may require prepregs or wet-layup techniques performed under vacuum pressure to minimize voids and align fibers with the direction of highest stress. Plastics, by contrast, can be formed in molds using heat and vacuum for large panels, or assembled from pre-made sheet stock cut and bonded into the desired geometry.

The distinctions between layup and molding are not cosmetic; they determine how long the parts take to produce, how consistent the results will be, and what skills the fabricator must develop. Fiberglass layups are, in practice, a craft in which the operator learns to manage resin distribution, trap air bubbles, and build up layers without creating warps. The control of thickness across a curved surface becomes a central concern, because too-thick sections may add unwanted weight, create stress concentrations, or hinder fitment around critical mounting points. With carbon fiber, the density of the fabric weave and the orientation of the fibers demand a meticulous plan. The orientation—whether fibers run along edges, or wrap around curves—governs how the panel responds to aerodynamic forces and how it resists bending or torsion under load. The cure stage often benefits from vacuum bagging and controlled climate to minimize porosity. Each technique demands a certain level of expertise and a separate set of tools, and the decision must be reconciled with the rider’s timeline and the project’s budget.

Finishing and painting are the final, transformative steps that translate a stiff, high-performance shell into a living part of a motorcycle. Regardless of the base material, sanding to a smooth finish, applying primer, and building up top coats are essential to protect against UV exposure and environmental wear. A well-executed paint job not only glazes the surface but also acts as a protective shield that extends the life of the composite underneath. Some riders seek a pure, high-gloss aesthetic that makes the weave of carbon fiber come alive; others prefer a satin or matte finish that emphasizes form over shine. The finishing stage also offers opportunities for functional design: integrated vents, subtle nubs for airflow, or add-on features like UV-protective clear coats that keep the colorfastness steady in the sun. In all cases, the interface between the fairing and the bike—the joint lines, the fasteners, and the way the panel attaches to the frame—requires careful alignment. A fairing that looks perfect on a static image can reveal misalignment or torsional movement when the bike is moving in a crosswind or undergoing a braking maneuver. Installation and testing then become the final analysis, confirming that the material choice holds its geometry under real-world loads and that the fairing does not intrude on braking performance, steering, wheels, or rider visibility.

An important nuance in the material conversation is the possibility of hybrids. Many builders blend approaches to optimize both cost and performance. A typical hybrid might use fiberglass as the primary structure, with carbon fiber reinforcements in critical load-bearing regions, or carbon fiber accents that reduce weight in exposed areas while keeping bulk in reserve for protection. Another common approach is to craft larger panels from ABS plastic for durability and then bond or insert carbon fiber inserts where stiffness is most beneficial. The challenge here is ensuring the different materials bond well and behave deterministically in service. Differential thermal expansion, moisture diffusion, and aging can all influence the bond line, so surface preparation, adhesion chemistry, and appropriate sealing become essential considerations in the plan. The result is a fairing that captures the benefits of multiple materials without inviting the complexity and cost of a fully monolithic CFRP shell.

The decision matrix you apply at the outset should consider not only weight and stiffness but also maintenance and repairability. Fiberglass remains a friendly option for riders who want the ability to repair at home, perhaps with resin and new cloth, or through a local shop that can sand, gelcoat, and repaint a damaged section. Carbon fiber, in contrast, demands a more precise repair approach. Damaged CFRP panels may require patching with compatible prepregs or reinforcements, and the repair may not yield a seamless match with an undamaged surface. Plastics offer repair options rooted in the forgiving nature of the material; a ding can often be filled and re-sanded, and most after-sales plastics are designed to be replaced as a whole piece when the structural integrity is compromised rather than repaired piecemeal. The decision, again, hinges on the rider’s philosophy: if one values long-term, low-maintenance ownership, plastics or fiberglass with durable resins may be the most practical choice. If one pursues ultimate performance with a willingness to invest in specialized craftsmanship, CFRP might be worth the commitment.

The practical realities of purchasing or fabricating fairings reinforce a broader point: material choices must align with safety and compatibility. The BMW manual and other safety guidelines emphasize that modifications to vehicle aerodynamics should never compromise visibility, braking performance, or handling. When you design or install fairings, check that vents, intake routes, and mounting points do not interfere with critical components. This is where the engineering mindset becomes essential. A well-chosen material is not merely light or strong; it is predictable in how it ages, how it responds to heat and moisture, and how it behaves under vibration. A great fairing is a quiet partner to the engine and rider, delivering efficient airflow without introducing resonant vibrations that could transmit through the frame or rider’s body. The ideal outcome is a shape that remains stable under gusts, a surface that sheds water cleanly, and a finish that resists chalking or fading for years of use.

For riders who want to see real-world examples of how these principles translate into product choices, a practical option exists within the aftermarket landscape. Consider exploring the BMW fairings category to observe how OEM-grade materials and precision manufacturing translate into durable, form-fitting shells that can serve as benchmarks for design and fitment. The catalog presents an opportunity to study how a brand integrates material performance with modular, bolt-on compatibility. Such exploration helps grounded builders understand what a well-executed fairing system should deliver: a precise fit, predictable alignment with existing mounting points, and surfaces that maintain their geometry across a wide range of speeds and conditions. This is not merely about aesthetics; it is about the material being a partner in the bike’s dynamics, contributing to stability, protection, and the rider’s confidence on the road. (Internal link: BMW fairings)

In summarizing the material landscape, the overarching message is clear. Fiberglass, carbon fiber, and plastics each carry a distinct promise. Fiberglass offers a balanced entry point: relatively light, affordable, and repair-friendly. Carbon fiber promises top-tier performance in stiffness and weight, but demands investment in process and price. Plastics provide resilience and mass-production compatibility, with a lower risk of catastrophic failure and easier replacement when styling or aerodynamics shift with the bike’s evolution. The best choice is seldom a single material; more often it is a tailored solution that recognizes the bike’s mission, the rider’s tolerance for complexity, and the project’s budget. The craft lies in harmonizing design intent with material behavior so that every line on the fairing serves a purpose—minimizing drag, protecting the rider, and carrying the visual language the motorcycle deserves.

As you move from concept through mold, layup, finishing, and installation, keep the conversation with your material honest. Ask what you are optimizing: speed, efficiency, durability, repairability, or a blend of all of these. Ask how you will maintain the integrity of the bond between panels and frames, how heat and sun exposure will affect the finish, and how you will address potential moisture intrusion in the lamination. Ask what equipment you have access to, and whether you will benefit from a hybrid approach that leverages strengths across materials. The chapter of material science in fairing fabrication is not a closed textbook; it is a living dialogue that evolves with every project. By approaching the craft with patience, respect for the material, and a clear set of goals, you can sculpt a shell that not only looks fast but behaves like it too, under real-world riding conditions.

For further reading and practical buying guidance on plastics and their performance characteristics in fairing applications, you can consult a thorough external resource that breaks down the types of plastics used in motorcycle bodies and how to choose among them. External resource: https://www.motorcycle.com/guides/how-to-choose-motorcycle-plastics/

Internal link used within the chapter for context and navigation: BMW fairings (internal): https://ultimatemotorx.net/product-category/bmw-fairings/

From Mold to On-Road Form: The Quiet Engineering of Motorcycle Fairings

The fairing is more than a shield against wind; it is an engineered canvas where form meets function, where aerodynamics, strength, and style converge to influence a bike’s behavior at speed. In the spaces between sketches and the first layup, skilled hands translate curves into tangible performance. A chapter on fabrication begins not with resin and cloth, but with a design that respects the motorcycle it must embrace. The goal is to create a shell that smooths airflow, reduces drag, channels cooling air where needed, and protects the rider, all while honoring the bike’s geometry and rider ergonomics.

This chapter moves from master model to mold, exploring material choices, surface fidelity, and the tradeoffs between fiber systems and resins. Fiberglass offers workability and forgiving repair; carbon fiber delivers stiffness and lightness but demands technique and cost. Plastics such as ABS provide drape and impact resistance but require careful finishing to maintain UV stability. The molding methods hand layup, vacuum bagging, and, in higher-volume contexts, spray-up or injection molding balance replication fidelity with manufacturability.

The transition from mold to finished fairing involves finishing and detailing: sanding, priming, color layers, and clear coats that resist sun, fuel, and abrasion. Beyond aesthetics, the finish also supports structural behavior, helping manage stiffness, edge radii, and seam integrity. Installation then aligns geometry with aerodynamics and rider ergonomics, testing fit against headlights, tanks, wheels, and exhaust routing. Iteration through bench tests and ride tests informs mounting points and panel shaping, culminating in a shell that feels integrated with the bike rather than bolted on.

Safety and standards frame the approach. A well-designed fairing respects rider visibility, ensures sufficient clearance, and behaves under load and vibration. Whether for DIY builds or OEM programs, the goal is predictable, durable performance that enhances speed, control, and comfort. The craft is a dialogue between model, material, and rider—an ongoing practice of listening to the bike’s geometry and translating that listening into reliable, expressive form.

Final thoughts

Understanding how to make motorcycle fairings effectively can elevate your business in the competitive motorcycle industry. By focusing on careful design, selecting appropriate materials, and mastering fabrication techniques, you can produce high-quality fairings that enhance both performance and aesthetics. Investing in this knowledge not only expands your service offerings but also appeals to a broader range of customers who value customization and quality. As you proceed in your journey, remember to prioritize safety, quality, and compliance with industry standards.