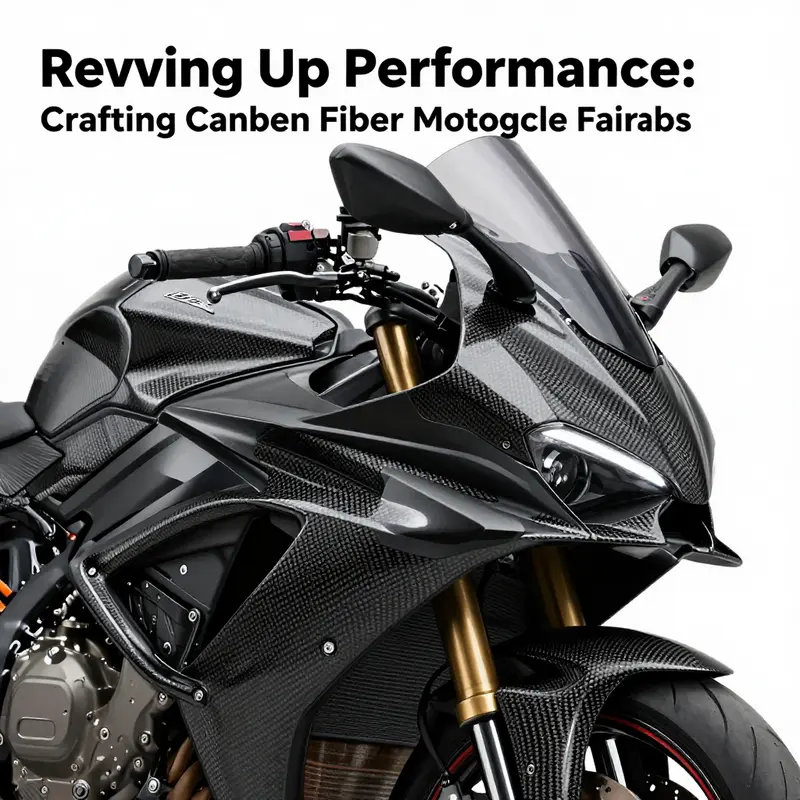

The motorcycle industry is evolving rapidly, with performance and customization becoming key drivers of consumer choice. Among the top innovations, carbon fiber motorcycle fairings stand out due to their lightweight properties and aerodynamic efficiency. As business owners look to expand their offerings or delve into customization, understanding the aligned design considerations, the manufacturing process, necessary safety measures, and current market trends is invaluable. This article will provide a comprehensive exploration of these critical aspects, empowering business owners to effectively engage with this burgeoning niche market.

Contours of Performance: Designing Carbon Fiber Motorcycle Fairings for Aero Efficiency and Structural Integrity

A motorcycle fairing is more than a shell clinging to a bike; it is a carefully engineered system that governs how air meets the machine, how loads travel through the chassis, and how the rider experiences speed, stability, and control. When designers embark on the path from concept to carbon fiber, they enter a space where aero dynamics, materials science, and aesthetics fuse into a single, purposeful form. The initial spark is a design brief that blends function and form, demanding that the final skin not only look the part but actively contribute to performance. In this context, every curve, vent, and junction becomes a choice with measurable consequences, and carbon fiber’s distinctive advantages create a canvas for innovation that few other materials can match. The journey begins in a CAD environment, where airflow, structural lines, and attachment points are tested before a single layer of fabric is laid into a mold. The exercise is not merely about reducing weight; it is about distributing stiffness precisely where it matters, while preserving or even enhancing the bike’s behavior at speed and in cornering. This integrated approach makes a design study far more than an exercise in sketching. It is a lifecycle of decisions that ripple through manufacturing, maintenance, and riding experience, and the best designs emerge from an iterative loop of simulation, prototyping, and real-world testing.

Aerodynamics, first and foremost, drives the conceptual shape of a fairing. Designers rely on computational fluid dynamics and wind tunnel data to shape profiles that manage the flow over the engine, rider, and frame. The object is to minimize drag and suppress turbulent wake that would otherwise increase fuel consumption or reduce stability at high speeds. But efficiency is not achieved by a single sweeping line; it is a tapestry of contour transitions, edge radii, and internal channels that guide air to critical paths. Optional air vents, intakes, and channels are not decoration; they are functional features aimed at cooling, reducing pressure buildup, and smoothing the pressure distribution around the front of the bike. At every stage, the design must consider how the airflow interacts with the rider’s body position, the windshield, and the bike’s geometry. The result is a fairing that seems to disappear at speed, shaping the air in a way that supports the desired ride quality rather than merely covering the machine.

Those aero goals are interwoven with a second, equally vital discipline: structural integrity. Carbon fiber offers a superb strength-to-weight ratio, but the fairing must withstand a range of demanding conditions. It must absorb and dissipate impact energy from light crashes or road debris, endure continuous vibrations, and maintain dimensional stability under heat and UV exposure. The design team chooses carbon fiber weaves and resin systems that align with the load paths the fairing will experience. Uni-directional prepregs or multi-axial layups provide directional stiffness where the loads concentrate—around mounting points, the connection to the head and tail sections, and along the upper edge that bears the brunt of wind pressure. The layup sequence becomes a language describing how power, torsion, and shear flow through the part. In plain terms, placement of plies is a negotiated compromise: more fibers in high-stress regions add strength, but extra plies increase weight and cost. The craft lies in shading the laminate with just enough reinforcement where it is needed, avoiding excess that would blunt the very gains carbon fiber promises.

Weight optimization is not a mere chase for lighter parts; it is a disciplined engineering exercise aimed at achieving the optimal stiffness-to-weight balance. Designers exploit the knowledge that carbon fiber can be laid up in complex internal geometries without adding bulk. They explore the use of sandwich constructions, where lightweight cores such as foam or lightweight honeycombs sit between carbon skins to deliver rigidity without unnecessary mass. These cores play a crucial role in tailoring bending stiffness and impact resistance. The distribution of material is therefore not uniform but carefully weighted toward regions experiencing the highest bending moments and torsional stresses. In practice, this translates into a fairing whose outer surface remains visually pristine while its inner structure carries the mechanical load with minimal mass. The result is a chassis partner that improves handling, steering response, and high-speed stability, all while contributing a crisp, taut feel through the handlebars and footpegs that riders expect from a well-tuned machine.

Manufacturing process and tooling constraints inevitably steer design decisions. The chosen fabrication route—hand lay-up, vacuum bagging, and autoclave curing—defines what is possible in terms of geometry, tolerances, and surface finish. Complex curves and features with undercuts demand sophisticated molds, often requiring generous draft angles to facilitate release. The mold itself becomes a kind of invisible partner in the design, one that must be dimensionally stable, dimensionally accurate, and capable of delivering repeatable results. The relationship between design and tooling is intimate: too aggressive a curvature can complicate resin flow and air removal, while overly shallow radii may compromise the visual appeal or the ability to achieve the desired aerodynamic behavior. The process also imposes practical limits on laminate thickness and fiber orientation. Real-world manufacturing cannot bend the ice cream scoop of a perfect theoretical layup into a flawless part without considering resin cure kinetics, vacuum integrity, and pressurization uniformity in the autoclave. The result is a design that honors performance goals while remaining manufacturable within realistic cost and time constraints.

Intimate integration with other components defines the fit, finish, and function of the final product. Fairings do not live in isolation; they must align with headlights, instrumentation, windshields, and mirror systems while also accommodating wiring harnesses and cooling ducts. The mounting points and joint geometry must be robust enough to resist the repeated loads of road vibrations and rider inputs, yet precise enough to maintain alignment across multiple sections of the fairing. This speaks to the art of tolerancing in composites, where the inherent variability of resin-rich laminae and the compression of the autoclave can affect overall dimensions. Designers therefore plan for acceptable tolerances and develop pragmatic strategies for assembly, such as locating stiffening ribs close to mounting interfaces or incorporating adjustable fasteners in strategic positions. When the fairing is finally assembled on the motorcycle, it should form a seamless silhouette that looks and feels integrated—the lines converge with the bike’s frame and glassy surfaces reflect the light with a purposeful sheen. The aesthetic and brand identity piece enters here not as a flourish but as a statement of engineering intent: brand cues, signature lines, and color logic are woven into the geometry rather than slapped on as decals. The interplay between form and function in this context becomes a visible marker of performance intent that enthusiasts instantly recognize, even in a still photograph.

The repairability and cost calculus of carbon fiber fairings also bubble to the surface in design discussions. Carbon fiber is resilient, yet not invincible. Repairs, when needed, often require specialized techniques and materials that can restore structural integrity without compromising the laminate’s long-term performance. Designers and fabricators therefore consider repair scenarios early in the design phase: how a damaged section can be patched, what spare reinforcement might be inserted, and how the repair would affect stiffness and aerodynamics. At the same time, the economic reality of carbon fiber work—material costs, labor intensity, and tooling expenses—shapes decisions about where to invest in reinforcement and where to accept a lighter, simpler patch. The overarching aim is to deliver tangible performance gains that justify the cost while ensuring the final product remains attractive to riders who demand both speed and style. In practice, that balance manifests as a fairing that looks the part, threads neatly onto a bike, resists the sun’s UV rays, and keeps its shape under the heat of spring sun and the chill of autumn evenings.

As the design hands off to manufacturing, the conversation naturally broadens to the lifecycle of the part. Designers pay attention to how the fairing will be built from start to finish and how the process can be optimized for consistency across batches. A well-considered design reduces variability in laminate thickness, resin content, and surface quality, which in turn translates to reliable performance in the field. This attention to process is not a luxury; it is a prerequisite for achieving repeatable results at scale, particularly when the goal is to produce fairings that are both light and strong while delivering a premium aesthetic that can help a rider stand out in a crowd. The design-to-production loop is therefore a continuous dialogue among aerodynamicists, structural analysts, toolmakers, and finish specialists. Each voice informs the others, and the outcome is a carbon fiber fairing that behaves predictably under high-speed loads, tolerates the rigors of real-world riding, and presents a finish that remains visually striking over years of exposure to sun, rain, and road debris.

For builders who choose to explore this field in depth, the path from concept to finished part can be richly rewarding but demanding. The practical realities—access to a vacuum bagging system, a controlled environment for resin cure, and substantial experience in composites—mean that for most riders, professional fabrication remains the most reliable option. However, the skills and insights gained from careful study of the design considerations discussed here are transferable to any scale of production, from boutique one-off builds to small-batch manufacturing. Even when a project begins as an artistic interpretation of speed, it quickly becomes a disciplined exercise in material science and mechanical engineering. The most compelling carbon fiber fairings you see on the road are those that have been shaped by this disciplined approach—an approach that respects air and energy as equally important, and that treats the material not as a fashionable surface but as an active contributor to the bike’s performance envelope.

To further explore related design directions and options in the broader ecosystem, consider visiting a contemporary catalog that emphasizes current offerings and configurations in 2023 models. This category, while not naming any single product, provides a sense of how modern fairings balance weight, stiffness, and form in ways that reflect the principles outlined above. 2023 new

For readers seeking a deeper, more technical dive into the fabrication steps and process controls that underpin high-quality carbon fiber parts, the following external reference offers a rigorous guide to what happens behind the scenes: a step-by-step exploration of making carbon fiber parts. Composites World guide This resource complements the practical considerations discussed here by detailing resin systems, cure profiles, and quality assurance checks that help ensure a consistently strong, light, and aesthetically pleasing final product. The integration of theory and practice—fusion of aerodynamics with material science, and design with manufacturing—remains the core thread that connects every stage of the journey from concept to high-performance carbon fiber fairing.

Weaving Velocity: The Engineering and Craft Behind Carbon Fiber Motorcycle Fairings

The allure of carbon fiber motorcycle fairings goes far beyond their sleek, glossy surfaces. They embody a marriage of science and handcraft, where minute decisions in material science ripple outward to affect speed, handling, and even the rider’s sense of connection with the machine. To understand how these parts come to life is to appreciate a discipline that blends design, process control, and artistry. It starts with an idea of how a shape should slice through air, then follows a careful choreography of steps that transform a tangle of carbon fibers and resin into a single, cohesive, aero-optimized skin that hugs the bike’s silhouette. Each stage—from digital concept to the final polish—carries its own demands, tolerances, and tradeoffs. The result is a structure that remains remarkably light, resists fatigue, and presents a surface capable of withstanding sun and rain while retaining a premium, almost sculptural look. This is more than manufacturing; it is a statement about how performance and aesthetics can be fused through disciplined technique and patient hands.

Design sits at the heart of the process, long before the first strip of fabric is laid into a mold. Engineers and designers begin with CAD models that translate aerodynamic theory into practical geometry. The aim is to optimize airflow around the rider and machine, reduce drag, and maintain or improve downforce where needed. The shape must also respect the bike’s chassis, ensuring clearance from moving parts, steering inputs, and the rider’s knees. In this iterative phase, small tweaks to ribbing, edge radii, and fairing overlap can alter a motorcycle’s trim and stability at high speed. This is the moment where computational analysis—whether CFD wind simulations or simple aero profiling—guides decisions, but it does not replace the tactile judgment that follows. The CAD environment feeds the mold shop with precise curves and planes, while the field of composites demands a tangible connection to how the material behaves under pressure and heat.

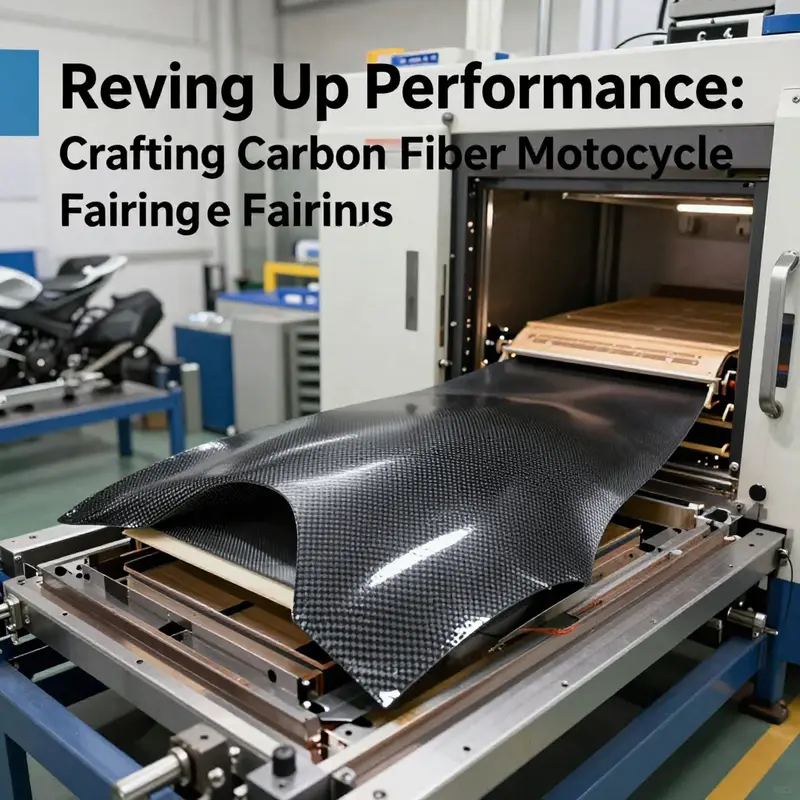

With the digital design approved, the real world curiosity begins: how does one capture the glossy, continuous form with layered sheets of carbon fiber? A mold must be produced that translates the digital dream into a physical, smooth surface. Molds are typically fabricated from fiberglass or aluminum, materials chosen for their predictable release characteristics and stability under heat. Before any carbon touches the mold, it is treated with a release agent—often a wax or polymer coating—that ensures the cured part can be extracted without the resin bond tearing or the surface sustaining scratches. The mold itself becomes a kind of silent collaborator, its surface finish dictating how perfectly the final fairing will reflect light and feel to the touch. The preparation phase, though seemingly mundane, is where the groundwork for reproducible quality is laid. If a mold is scarred, nicked, or inconsistently polished, every subsequent layer risks inheriting that imperfection.

The actual laying of carbon fiber stands as a test of manual skill and spatial awareness. High-strength carbon fiber fabric is cut to shape and then laid into the mold by hand. This is not a mundane task of filling space; it requires careful attention to fiber orientation, ply count, and the way fabric conforms to complex contours, such as edges that taper toward the nose or sweep along the bike’s flank. Wrinkles are the enemy here, for they become stress risers and surface blemishes. The layup process must balance the need for tight fiber-to-resin contact with the desire to avoid excessive stacking that would dull the data-driven goals of stiffness and weight. The artisan’s touch matters as much as the engineer’s calculation because every wrinkle, overlap, or misalignment subtly affects the anisotropic behavior of the composite. When done well, the fabric layers nestle into the mold with a quiet confidence, like a carefully tuned fabric lying flat across a seam, ready to be bound together.

Resin application follows, and this is where the drama of composites unfolds. Epoxy resin saturates the fiber, acting as the binder that transfers loads between fibers and locks them into the correct orientation. The resin’s viscosity, cure time, and compatibility with the chosen carbon plane all influence the final performance. Some practitioners apply resin by brushing; others use more controlled techniques that minimize capillary gaps. The goal is thorough wetting of every thread without creating excessive resin-rich zones that would add unnecessary weight. Once the resin is distributed, the entire assembly is sealed within a vacuum bag. The bag forms a flexible envelope that, when evacuated, pulls the layers tight against the mold. The vacuum pressure removes air pockets that would otherwise become voids, which are the enemies of mechanical integrity. The process is not simply about removing air; it is about achieving a uniform fiber-resin distribution that allows the composite to manifest its best combination of stiffness and lightness under real-world loads.

Curing is the crucible in which the material’s character is finally baked into place. The sealed mold typically goes into an autoclave, a pressurized oven that applies both heat and uniform pressure across the surface. In an autoclave, resin cures under meticulously controlled conditions, encouraging complete resin infusion and eliminating micro-voids that might compromise strength. The temperature and pressure profiles are chosen to align with the resin system and the fiber layup. The result is a dense, well-wetted composite with a superior strength-to-weight ratio and a smooth, nearly flawless surface finish. Autoclave curing is a hallmark of premium, performance-oriented parts, but it is also technically demanding. For applications where an autoclave is not available, a sealed vacuum-bag setup combined with careful heat application can still deliver high-quality results, albeit with potentially more variability in laminate density. The choice of equipment, then, is not merely about speed or cost; it is about the level of performance certainty the builder seeks for high-stakes riding conditions.

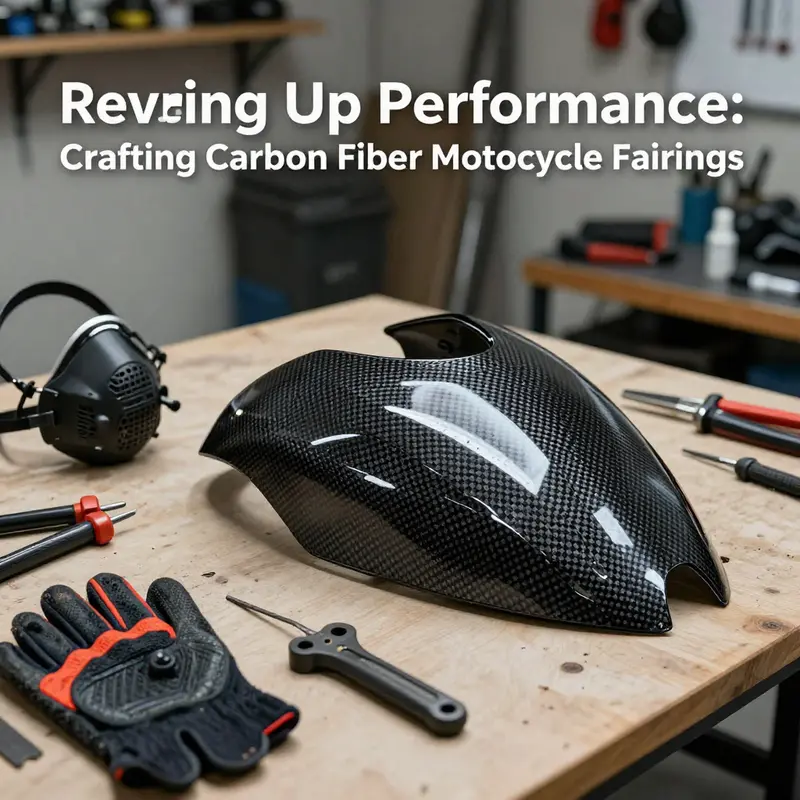

When the resin hardens, the part is removed from the mold and subjected to post-curing and finishing. Demolding requires a steady hand and an eye for the final surface’s fidelity to the intended shape. The next steps—trimming to fit, sanding to remove any mold marks, and polishing to reveal a glassy finish—are where the craft truly becomes visible. A masterful finish does more than please the eye; it protects the resin matrix and fiber from environmental assault. A clear coat or pigment layer seals the surface, guarding against UV exposure and abrasion while contributing to the bike’s visual effect. A well-executed surface finish highlights the weave of the carbon fiber, turning the fairing into a functional sculpture that reflects the rider’s appreciation for precision workmanship.

The educational value of the process extends beyond aesthetics. The way the laminate is oriented and how many plies are used at critical regions directly influences how the part behaves under aerodynamic loads and structural stress. In regions that experience high dynamic pressure, more plies or specific orientations can increase shear stiffness and panel rigidity, reducing flutter and enhancing handling stability. Designers must also consider impact resistance, especially for fairings that may encounter debris. Weight is a constant consideration, but so is the distribution of weight; carbon fiber can deliver a high stiffness-to-weight ratio, yet poor laminate design can still yield a part that feels hollow or rattles under vibration. The skill lies in balancing weight savings with the mechanical demands of real-world riding—acceleration, deceleration, cornering, and the fatigue loads that accumulate over thousands of miles.

Quality control is not an afterthought but a continuous thread throughout the process. Inspectors examine the surface for resin-rich zones, air voids, and surface defects that could propagate under load. Non-destructive testing techniques may be employed to identify subsurface imperfections, though in many workshop environments, visual inspection and surface flatness checks are the first line of defense. The best practice involves setting up process discipline early: consistent layup templates, controlled resin flow, and a uniform cure cycle. When the factory or custom shop adheres to strict process controls, the resulting fairings demonstrate repeatable performance and an elevated sense of reliability that riders crave when they push a machine to its limits.

This narrative of manufacturing is not simply about chasing lower weight or a satin finish. It is about a philosophy that recognizes carbon fiber as a material with a memory. The fibers remember how load travels along the laminate, and the resin remembers the heat and pressure it was exposed to during curing. The symbiosis of these memories defines how a fairing behaves in the wind, how it resists flex under gusting air, and how it coexists with the bike’s frame and ergonomics. In real-world terms, that means a rider can lean into a corner with more confidence, knowing the fairing’s reaction to air pressure and body input has been engineered, not merely invented. The chapter has moved through CAD to busting out the first panels from their molds, but the broader implication endures: carbon fiber fairings are not just shells; they are performance systems that convert aerodynamic theory and material science into tangible riding experience.

For enthusiasts who crave a sense of direct involvement, there is a clear path from idea to finished piece within reach of skilled hobbyists as well as professional workshop teams. DIY enthusiasts who choose to make their own fairings should recognize the level of equipment required. A proper vacuum bagging system and a reliable heat source are essential, but more important is the readiness to engage with composites at a hands-on, iterative level. The learning curve is steep, and the risk of waste is non-trivial, but the potential rewards extend beyond cosmetics. A well-executed project teaches discipline in material handling, precision in measurement, and a deeper appreciation for the discipline and patience that high-performance engineering demands. For most riders, the safer and more consistent path remains professional fabrication, where controlled environments and skilled technicians bring the most robust, repeatable outcomes.

In applying these insights to the broader article, the fairing becomes less a simple panel and more a carefully engineered interface between rider, machine, and environment. Its success depends on the alignment of design intent, manufacturing discipline, and finishing finesse. The result is a composite skin that not only reduces weight and improves aerodynamics but also frames the rider in a sculpted, confident silhouette as the bike moves through air. The craft, the science, and the artistry converge in a single, purpose-built component. For readers who want to see how this philosophy translates into market offerings, a look at relevant fairing categories can provide practical context about fit, style, and compatibility: BMW fairings catalog. This link offers a representative sense of how frame geometry and component integration drive the shaping and joining of panels across different models, illustrating how the same fundamental manufacturing principles scale to varied shapes and sizes as designers adapt form to function.

As the chapter closes on this material journey, it is worth reflecting on how the process pattern—design, mold, layup, cure, finish—echoes the larger narrative of modern engineering. Carbon fiber fairings are not a single moment of assembly but a sequence of tightly controlled decisions, each tuned to the rider’s needs and the machine’s performance envelope. They require a patient, methodical approach to achieve consistency and a level of craftsmanship that makes each panel feel special. And as with any composite structure, the final product embodies the story of its making: the careful placement of every ply, the exacting pressure that eliminates voids, and the final glaze of resin and pigment that seals in both beauty and resilience. When these elements align, the resulting fairing does more than cover; it directs, it protects, and it communicates through the quiet power of precision. For readers seeking more technical depth beyond the overview, a foundational reference offers a step-by-step exploration of carbon fiber part production that complements the practical details shared here. It provides a broader context for the techniques described and invites deeper study into the chemistry, physics, and manufacturing science that underpins modern high-performance composites.

External resource: Composites World step-by-step guide

Engineering Safety and Craft: The Hidden Rigor Behind Carbon Fiber Motorcycle Fairings

Carbon fiber motorcycle fairings sit at the intersection of high science and hands-on artistry. They are not merely shells that make bikes look leaner or ride smoother; they are engineered systems where every layer, every junction, and every protective coating contributes to the overall performance. In the realm of carbon fiber, the goal is a structure that blends remarkable strength with astonishing lightness, a combination that improves handling, acceleration, braking response, and aerodynamics. Yet achieving this ideal is possible only when design intent and manufacturing discipline align from the first CAD model to the final finish. What follows is a narrative that treats carbon fiber fairings as a disciplined craft. It traces how an idea becomes a shaped, resilient layer through careful material choice, precise tooling, and rigorous safety practice. The journey begins with design—an exercise in predicting how airflow will meet the fairing, how the panel will resist impact or vibration, and how weight savings translate into real-world performance. In the digital workspace, engineers manipulate contour, thickness, and rib placement with a sensitivity that mirrors wind tunnel insights, even when the test rig is a custom wind box built from practical components rather than a full-scale facility. The CAD model is more than a pretty surface; it encodes the aerodynamics and the structural pathways. Soon the design graduates to a physical form via a mold, a critical artifact that defines the final appearance and the fidelity of the carbon layup. The mold is a negative form, typically built from glass fiber or epoxy resin composites, chosen for dimensional stability and surface quality. A release agent is applied to ensure clean demolding, so the first true carbon layer can cling to the intended geometry without tearing or dragging. The surface finish of the mother mold, the plug, and the mold cavity itself becomes a latent agreement between design and manufacturing. Any imperfection here will translate into visible ripples or misalignment on the finished fairing. Once the mold is prepared, the layup begins. The build-up of carbon fiber fabric is a choreography, not a random assembly. The fabric is laid in successive plies, each orientation selected to balance torsional stiffness, flexural strength, and impact resistance in the directions most consequential to a motorcycle’s dynamic loads. In a wet layup, each ply is brushed or rolled with epoxy resin, a binder that negotiates between wetting the fibers and controlling resin-rich zones that can impede performance. In prepregs, the resin is pre-impregnated into the fabric with precise content and a defined pot life, enabling repeatable, high-fidelity parts. The method chosen—wet layup, prepreg, or a resin infusion approach—depends on facilities, desired fiber architecture, and the scale of production. All paths share a single essential truth: resin content must be controlled, air must be expelled, and moisture kept at bay. The layup then enters a vacuum bag, where the essential act of compaction takes place. The bagging system, with its permeable breather layers and a seal that keeps the resin-rich air inside the bond line from escaping, is a quiet but indispensable ally. This stage sets the stage for the key arithmetic of carbon fiber: the removal of air, the elimination of microbubbles, and the establishment of a consistent, consolidated laminate. Vacuum alone does not finish the job; it is paired with heat and pressure in a controlled cure environment. A modern autoclave—an industrial oven designed to apply uniform heat and pressure—ensures the resin cures evenly and the plies consolidate without delamination. The autoclave is not a luxury but a practical instrument for reliability; its role is to push resin flow and fiber compaction to a level that manual methods cannot consistently achieve. In environments where an autoclave is unavailable, alternative routes—such as carefully controlled oven cures or resin infusion with meticulous vacuum management—can still yield high-performance components. The curing cycle—its temperature, duration, and ramp rate—must be matched to the resin system and the geometry of the fairing. Even slight deviations can alter resin crosslinking, which in turn may affect impact resistance or UV stability. After the cure, the part is removed from the mold with care. The nest of carbon fiber is still relatively fragile when warm, and the transition from laminate to finished component requires restraint and handling discipline. The trimming stage follows, where the fairing is trimmed to fit within the bike’s frame contours and mounting points. This is a moment where precision, not brute force, dictates the final fit. A clean edge is more than cosmetic; it reduces snag points and minimizes crack initiation under load. The next frontier is surface preparation and finishing. Sanding, polishing, and sealing with a clear coat not only sharpen the aesthetic but also shield the laminate from UV exposure and abrasion. A proper clear coat contributes to color stability and gloss retention, guarding the appearance against the sun’s relentless rays. The surface work also addresses micro-defects that survived the curing process. These may include slight resin pockets or fiber misalignments, which are carefully corrected through progressive sanding and a final polish. The result is a fairing whose surface integrity is as important as its internal structure. The overall manufacturing sequence—design, mold, layup, vacuum, cure, demold, trim, and finish—frames the dialogue between an engineer’s intent and a craftsman’s hand. Yet this dialogue is incomplete without acknowledging safety as an integral dimension of the craft. The materials used in carbon fiber composites, along with their processing, carry hazards that demand vigilance. The epoxies and reactive curing agents that bind carbon fibers are potent irritants and can pose long-term health risks when inhaled or absorbed through the skin. In most shops, a full-face respirator with an organic vapor cartridge is the baseline respiratory protection, coupled with a dedicated ventilation strategy that regulates the capture of fumes at their source. Eye protection is non-negotiable because resin splashes can cause rapid, painful injury. Gloves—preferably nitrile or neoprene—provide a barrier against skin sensitization and chemical burns, and full-sleeve garments prevent inadvertent skin contact during handling and layup. Hearing protection becomes essential when power tools come into play, especially during grinding and sanding, where decibel levels can exceed comfortable thresholds. PPE is the first line of defense, but the second line—the workshop environment—defines the baseline risk in practical terms. The work area needs robust local exhaust ventilation or a well-planned general ventilation scheme that moves fumes away from the operator and disperses them safely. It is critical to avoid enclosed spaces for resin work; a simple carport or an unventilated garage can transform into a hazardous chamber if fumes accumulate. Fire safety is another pillar. The materials involved—fibers, resins, and solvents—are flammable, and all ignition sources must be kept well away. A dry powder extinguisher, properly rated for electrical and hydrocarbon fires, should be within easy reach. The floor should be kept clean and dry, with sacrificial protective coverings to capture resin drips and prevent slip hazards. A dedicated, non-porous surface becomes the staging ground for resin mixing and layup, while a separate, well-ventilated area hosts finishing and sanding to minimize exposure to airborne particulates. The tools themselves demand respect. Molds demand precise care; any surface imperfection can imprint on the carbon laminate, turning a smooth fairing into a mirror of flaws. For mold cavities, a high-quality plug and a release agent are essential. The release agent ensures demolding without deformations, which is crucial for preserving the intended contours and mounting interfaces. The layup requires clean tools—disposable spatulas, brushes, and blades that avoid introducing contaminants. Resin mixing is a ritual of measurement and timing: components must be weighed accurately, mixed in appropriate containers, and used within workable pot life to ensure proper viscosity and lamination behavior. Vacuum bagging is itself a skill. The seals must be airtight, the breather materials properly placed, and the bag free from folds that trap air. Any leak or wrinkle can create voids that undermine the laminate’s stiffness and strength. The autoclave, when used, demands attention to preheating, pressure ramp, and cooling. A mismanaged cycle can introduce thermal gradients that crack the laminate or degrade the resin network. For facilities without an autoclave, resin infusion under vacuum in a controlled environment can approximate the benefits of pressure-assisted curing. In these scenarios, the operator carefully manages resin flow, fiber wet-out, and resin-rich zones to avoid dry spots that would create weak points. The post-cure phase invites another set of precautions. Demolding should occur with protective gloves and support jigs to prevent accidental damage. Finishing tasks—sanding, feathering edges, and applying a clear coat—demand a dust-controlled environment and appropriate respiratory protection because ultrafine particles and solvent vapors can linger. The finishing steps also test the integrity of the mold release and the restraint of the laminate. A scratch on the surface during finishing can become a portal for moisture and UV-induced degradation over time, so every stroke is measured and deliberate. Throughout this sequence, quality control acts as an ongoing discipline rather than a final inspection. Laminate thickness, surface flatness, and edge geometry are checked against the design intent. Any deviation prompts root-cause analysis: Was the fiber layup too coarse? Did resin bleed into a critical cavity? Was the cure too hot or too short? The aim is not perfection in the abstract but reliability in service. A well-made carbon fiber fairing carries the capability to withstand aerodynamic loads, resist impact damage, and endure the heat generated by the engine and the sun, all while contributing to the motorcycle’s overall performance envelope. The craft is also a practical exercise in anticipated service life. Carbon fiber, while remarkably resistant to corrosion and fatigue, is not impervious to impact and environmental exposure. UV exposure, abrasion, and chemical attack from cleaners or fuel spills require protective measures and appropriate maintenance routines. A clear coat not only brings a gloss that emphasizes the material’s weave and depth but also defends the laminate from the sun and from minor abrasions that otherwise would dull the surface with time. This makes the finishing phase not a cosmetic afterthought but a functional barrier that extends the fairing’s life and preserves its aerodynamic profile. Underpinning all this is a recognition that carbon fiber fabrication is a learned practice. It benefits from the guidance of established safety principles and the shared wisdom of a community that values meticulous, repeatable processes. The field rewards those who balance ambition with prudence, who scale their ambitions through incremental improvements, and who treat every layup as a potential test of a design’s viability. For readers who want to contextualize these practices within a catalogued landscape of fairings, a broader look at the market provides useful reference points. For instance, one can explore a wide range of fairing categories to understand mounting interfaces, compatibility footprints, and aesthetic choices across different bike platforms. Honda fairings, for example, serve as a useful reference frame for shape and fitment considerations while reminding us that a well-executed fairing is as much about precision and compatibility as it is about the resin chemistry and vacuum dynamics described here. You can peruse a broader selection at Honda fairings to understand how designers translate a design concept into a practical, rideable option that respects the original chassis geometry. This is not a call to imitation but a reminder that design thinking travels across brands and formats, and safety protocols travel with it, ensuring that the craft remains safe and sustainable regardless of the chosen path. The safety framework and equipment considerations discussed above are not merely a grocery list; they are the operating system that enables the rest of the process to function with predictability and confidence. A well-equipped shop with clear safety norms will tolerate ambitious experiments and encourage disciplined execution. It is through this disciplined approach that riders, engineers, and makers can push carbon fiber fairings toward new frontiers—lighter, stiffer, and more integrated with the bike’s aerodynamics—without compromising health, safety, or long-term performance. In the larger arc of the article, this chapter anchors the technical discussion in human factors: the people who design, mold, lay up, cure, and finish these components, and the environments that make safe practice possible. It is a reminder that the excellence of carbon fiber parts rests not only on the equation of fibers and resin, but on the ethics of safety, the rigor of process control, and the craftsmanship that makes a fairing feel inseparable from the motorcycle it cloaks. For those who seek a deeper technical guide to the steps and controls involved in making carbon fiber parts, several professional references illuminate the stepwise, evidence-based approaches that ensure quality and safety across the lifecycle of the part. External readers may consult the comprehensive safety-focused guide linked in the resources at the end of this chapter for further grounding in best practices and procedural workflows. See the external resource here: https://www.motorcyclefairingguide.com/safety-guide. The integration of these practices—design fidelity, mold integrity, layup discipline, controlled curing, and rigorous safety—frames carbon fiber fairings not as an audacious material experiment, but as a disciplined craft that honors performance goals while protecting the people who bring the concept to life. The chapter ends not with a conclusion, but with a continuity: the idea that safety is not a checkpoint but a core capability that evolves as the materials, tools, and techniques advance. The fairing’s value, after all, rests on a balance between structural resilience, aerodynamic efficiency, and the health and safety of the technicians who build it. In this sense, the craft is an ongoing conversation between design aspirations and practical safeguards, a dialogue that keeps the science of composites honest and the art of making carbon fiber motorcycle fairings thriving, responsible, and enduring.

Shaped for Speed: The Craft, Innovation, and Market Momentum Behind Carbon Fiber Motorcycle Fairings

The pursuit of lighter, stiffer, and more aerodynamically efficient shells has turned carbon fiber motorcycle fairings from mere covers into statements of engineering prowess. When riders chase better performance, they are not simply chasing horsepower; they are chasing the feel of a machine that responds with less lag, cuts through air with minimal drag, and carries the rider into a more immersive, connected experience. Carbon fiber’s appeal rests on a simple truth rendered in a sophisticated way: extraordinary strength at a fraction of the weight. But this advantage is earned through a disciplined process that blends modern composites science with decades of craftsmanship. The fairing project begins long before the first strand of carbon fiber is laid in a mold. It starts with design—an iterative dance between form and function. Designers use CAD to sculpt a shape that reduces parasitic drag, manages pressure differentials around the bodywork, and respects the rider’s posture and line of sight. They simulate airflow, test structural loads, and anticipate maintenance access. This is not vanity shaping; it is a careful integration of aerodynamics, rigidity, and serviceability. In this stage, the rider’s needs are translated into a shape that will later become a complex sandwich of materials. Even the most ambitious aesthetic goals are constrained by how the panel will behave under real-world wind loads, how it will endure temperature swings, and how it will be repaired if a panel experiences impact in the wild. The design phase also considers compatibility with existing frames and subframes, and it leaves room for a precise fit across a range of production tolerances. The result is a digital model that captures the essential performance envelope: where the fairing should contribute to downforce, where it should direct air toward radiators or around the rider’s body, and how it will interact with other components under dynamic loading.

Once the digital design is locked in, the work moves into the physical realm: creating a mold that can faithfully reproduce the final shape. The mold is typically constructed from robust materials such as fiberglass or epoxy resin composites, chosen for their rigidity and surface finish. A release agent is applied to ensure the carbon fiber part can be removed cleanly after curing, and the mold is meticulously inspected for surface imperfections that could telegraph through to the finished panel. This stage is a quiet kind of sculpture, a prelude to the layup that will define the fairing’s lightness and strength. The layup itself is where the material science comes to life. Thin, carefully cut layers of carbon fiber fabric are laid into the mold in a precise sequence. The orientation of each layer is deliberate: fibers aligned with the anticipated stress paths to maximize torsional stiffness and resist bending. The fabric is then wetted with a resin—most often an epoxy—that serves as the binder and protects the fibers from environmental attack. The layup, once fully formed, is usually placed in a vacuum bag. The bag is sealed to remove air and compress the layers together, which helps eliminate voids and centers the resin within the weave. This step bridles the layup with the pressure needed to coax every filament into alignment with the design’s intent. The most demanding phase follows: curing. In an autoclave, the layup is subjected to controlled heat and pressure. The autoclave’s atmosphere forces resin to flow and cure uniformly, driving out microscopic air pockets and ensuring a dense, consistent laminate. The resin’s chemistry and the pressure profile determine the final mechanical properties, including impact resistance and modulus. With the cure complete, the part is removed from the mold and begins its transition from the raw composite to a surface ready for assembly. It is trimmed to final dimensions, and any flash or excess material is removed with precision. Finishing then begins. Sanding smooths tool marks and rough edges, while polishing enhances the surface gloss. A clear coat or protective top layer is applied to shield the resin from UV exposure and abrasion, preserving the striking mirror-like sheen that is part of carbon fiber’s allure. The finishing stage is also about durability; the film or clear coat adds a shield against weathering and helps the color or weave remain vibrant over years of riding in varying climates. The artistry of finishing matters as much as the engineering of the layup because it communicates quality to the eye and to the touch. In this regard, the market has increasingly rewarded high-polish finishes that convey consistency across a product line. The narrative fans out here into the broader ecosystem of customization. Enthusiasts and professionals alike are pushing beyond stock shapes to craft unique silhouettes that reflect personal taste while maintaining or enhancing performance. The material has become a canvas for expression, with carbon fiber accents integrated into various components—panels, fender accents, air-guiding shrouds, and tail sections—creating a cohesive, high-end appearance without sacrificing the weight savings. The emphasis on aesthetics has grown in tandem with the technical sophistication of the materials being used. Advances in polymer blends and resin systems allow lighter weights, improved impact resistance, and more predictable finishes. A modern carbon fiber layup can incorporate subtle color through tinted resins or can be complemented by painted finishes that maintain the visual depth of the weave beneath a protective coat. The high polish that many custom builds now showcase is not merely cosmetic; it is a signifier of craftsmanship. For customers, a glossy surface that reveals the weave with a uniform gradient across panels communicates a level of care and attention that few other composites can offer. This demand for superior finishes has given rise to collaborations and restorative projects that fuse modern materials with vintage aesthetics. Across the market, story-driven builds showcase how carbon fiber can be used to reinterpret classic lines while preserving original silhouettes. Military-grade clarity is possible when old icons are revived with modern engineering, and the result is both performance-oriented and visually compelling. These collaborations emphasize that carbon fiber fairings are as much about identity as they are about speed. The market response to this shift has been robust. Carbon fiber has moved from niche to mainstream in premium fairing options, becoming an almost standard expectation for riders seeking a performance edge. The conversation today centers on how best to balance weight reduction with stiffness, how to optimize airflow with shape, and how to maintain durability during everyday riding or occasional track sessions. In this context, the role of advanced materials expands beyond sheer weight savings. The industry now experiments with blends that push the envelope of toughness and environmental resistance. These blends may include specialty polymers or resin systems designed to retain rigidity at elevated temperatures and resist the degradation that heat from the engine and sun exposure can otherwise cause. The practical benefits of carbon fiber fairings extend into maintenance as well. While a lighter composite can pose challenges in repair compared with traditional plastics, modern repair techniques and resin systems have grown more ductile and forgiving. The ability to repair a small crack or chip without sacrificing the integrity of the entire panel is increasingly feasible, provided repairs are performed by skilled technicians who understand the microstructure of the laminate. Yet many riders still choose to source professionally fabricated carbon fiber fairings. The reason is simple: the investment in the right tooling, safety gear, and skill set maps directly onto outcomes that are safer, more predictable, and longer lasting. The equipment required to produce top-tier parts—a vacuum bagging system for subtle consolidation, a reliable resin system, and, ideally, an autoclave—represents a significant commitment. For most riders, this is a decision governed by risk management, time, and expertise. DIY enthusiasts who embark on carbon fiber projects should approach the craft with respect for material behavior, process control, and safety. Carbon fiber layups demand meticulous handling to avoid inhalation of dust from sanding and to manage the risks associated with resin fumes and high-temperature curing. They also require a disciplined quality control mindset: checking for air voids, misalignments, or resin-rich zones that could compromise stiffness or surface finish. In the broader market, this discipline translates into a robust product ecosystem. As manufacturers expand their lineups, they offer varied grades, finishes, and design configurations that allow riders to tailor performance and appearance to personal preferences. The trend toward customization has deepened as brands and shops collaborate with artists and designers, seeking to bring a level of artistry to high-performance engineering. Even within the same chassis architecture, you can encounter multiple finish options—ranging from highly reflective gloss to semi-gloss textures—that suit different climates and maintenance expectations. The market’s momentum is further shaped by an increasingly interconnected consumer base that shares knowledge, project outcomes, and troubleshooting tips. Information flows through online communities, professional networks, and design forums, feeding a feedback loop that pushes manufacturers toward better resins, more predictable curing cycles, and easier fitment processes. In this ecosystem, the choice between full-fairing assemblies versus modular panels becomes a strategic one. Fully integrated fairings deliver the most substantial aerodynamic advantages but demand the most precise fit and engineering integration. Modular systems, by contrast, offer more customization latitude and potentially easier repair pathways, though they may introduce small inefficiencies in airflow if not designed with care. The decision often rests on the rider’s goals: ultimate track performance, long-haul comfort, or a balance of both. The practicalities of market offerings are also about accessibility. While professional fabrication shops can deliver flawless, championship-level shells, a growing number of riders seek options that align with hobbyist skill sets. The availability of precision-cut carbon fiber kits, detailed layup instructions, and supportive guides means motivated enthusiasts can engage with the process more deeply than before. However, this accessibility comes with caveats. Carbon fiber is more demanding than conventional materials in terms of handling, curing, and surface finishing. A misstep in vacuum sealing or resin ratio can lead to fiber wrinkling, resin-rich zones, or a surface that fails to hold gloss. The most successful outcomes, therefore, emerge from a blend of expertise, appropriate tooling, and a measured approach that respects the material’s behavior. The market’s ongoing evolution also benefits from educational resources that demystify the process. Industry guides, technical articles, and hands-on workshops help translate the science of composites into actionable steps for builders and riders alike. For those who want to see how theory translates into practice, a reliable reference is the broader technical literature that explains the step-by-step processes of carbon fiber fabrication. Access to these resources can deepen understanding of how to optimize tool paths, layer orientations, and curing schedules to achieve predictable results. In sum, the current landscape of carbon fiber motorcycle fairings mirrors a field that is at once highly technical and richly expressive. It reflects a growing appreciation for materials that fuse performance, durability, and aesthetics in ways that can be both technically rigorous and artistically compelling. The trends in customization—ranging from advanced materials and high-polish finishes to collaborative restorations and vintage-inspired reinventions—signal a market that values not only weight savings but also the identity and character that carbon fiber allows riders to project. In this context, choosing the right route—professional fabrication, collaboration with skilled restorers, or careful DIY with appropriate safeguards—becomes part of the rider’s ongoing narrative about what their machine represents. And as technology evolves, so too will the ways in which fairings are designed, cured, and finished, ensuring that carbon fiber remains a material that is as functional as it is aspirational. For a broader view of how these developments translate into real-world product lines and performance outcomes, consider exploring additional technical reading and official design case studies from the industry.

For deeper technical context and practical fabrication guidance, a detailed step-by-step guide to carbon fiber parts is available here: https://www.compositesworld.com/articles/step-by-step-guide-to-making-carbon-fiber-parts

Final thoughts

As the motorcycle industry continues to embrace advanced materials like carbon fiber, understanding design, manufacturing, and market trends is crucial for business owners seeking to remain competitive. By incorporating carbon fiber motorcycle fairings into their offerings, businesses can capitalize on the demand for lightweight performance and customization options. Engaging with this evolving market not only enhances product lines but also caters to the growing community of enthusiasts eager to personalize their rides.